by Nanore Barsoumian

(www.armenianweekly.com, January 22, 2013) – “It’s been 10 years that I’ve been out of the country. Life is very hard in Armenia; there are no jobs over there,” Lilit1, 53, told the Armenian Weekly. “Women worked very long hours—we worked more than men—but were paid very little. One person would do three people’s jobs, but would get paid one person’s salary. It was very hard to keep a family.”

Lilit is one of around one million people who have left Armenia since the country gained its independence in 1991. Blockades by two neighbors—Turkey and Azerbaijan—coupled with the Nagorno Karabagh War paralyzed the country economically. Armenia hemorrhaged about one fourth of its population within the first decade. The emigration rate, although reduced, still continues to alarm observers. According to the World Bank, based on 2010 figures, 28.2 percent of Armenia’s population—or 870,200 persons—have emigrated.2 Some have referred to it as a crisis, a disaster, and a serious threat to national security. For Lilit, it means a family torn apart, and a homeland unable to sustain her.

Lilit worked at a privately owned bakery in Yerevan for 10 years, baking bread. Despite her hard work, she could not seem to save any dram. “I used to work about 24 hours a day, sleeping while the bread baked. There were days I wouldn’t go home or sleep. If the owners wanted us to work long hours, we had to, in order to keep our jobs,” she said. The long hours yielded a pitiable salary for Lilit—somewhere between $50 and $60 a month—as she struggled to cover the family expenses that also included the needs of her three teenage children. “We would buy food and bread with loans. The girls were young and wanted to dress nice. We had to borrow money until the paycheck arrived; we’d pay back our debt, and then the cycle would resume. There were many others in my situation. Whoever could leave the country did so to find work and support their family. It seems to me things are still the same,” she said in resignation.

For love or security

Lilit and her family considered emigration as a last resort, but when an Armenian-American showed interest in Lilit’s daughter, then in her 20s, the family believed it was a path to salvation. It did not matter that the man was twice the daughter’s age, as long as he could take her abroad. The couple married, despite Lilit’s objections. She had envisioned a different future for her daughter. “We were a poor family. In Armenia, if you’re poor, it’s hard to marry off your daughter. My husband wanted for my daughter to move to the States as that would also be a way out for us.”

Lilit’s daughter was married within 15 days of meeting her husband. “She was a sacrifice for our salvation,” said Lilit, adding, “This is common in Armenia. Many people marry off their daughters to men from abroad so that they can get out and help in some way, whether financially, or if the parents are old, perhaps get them out as well.” Lilit’s daughter moved to the U.S. 12 years ago. She has since separated from her husband, and lives with her three young children.

Poverty

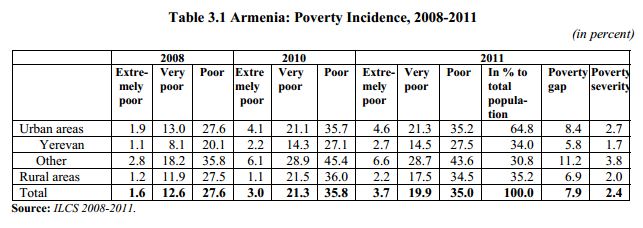

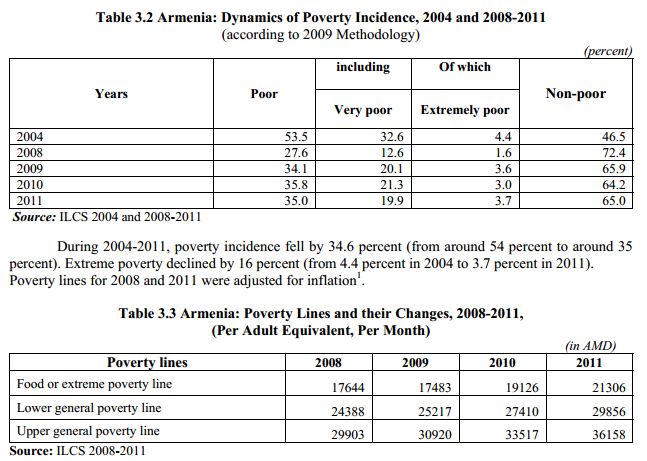

In 2011, over 35 percent of Armenia’s population was poor (that number was 35.8 percent in 2010), of which 19.9 was very poor, and 3.7 percent was extremely poor, according to the 2012 Integrated Living Conditions Survey. The “poor” are defined as those whose consumption is below the upper general poverty line; the “very poor” below the lower general poverty line; and the “extremely poor” or undernourished below the food poverty line. In 2011, the general poverty lines for the poor, the very poor, and the extremely poor were estimated to be AMD 36,158 (USD 97.1) a month, AMD 29,856 (USD 80.2) and AMD 21,306 (or, USD 57.2), respectively.

According to the report, “Just in two years (2009-11) some 250,000 people became poor as compared to 2008, thus raising the number of the poor in 2011 to around 1.1 million (per resident population); over the same period, some 240,000 became very poor, thus raising the number of the very poor to 650,000. In those 3 years, around 70,000 became extremely poor, thus raising the number of the extremely poor in 2011 to around 120,000” (see figures 1, 2, and 3 below).

Migration rate, a contentious topic

Currently, analysts rely on estimates, extrapolations, and incomplete and often contentious data when discussing the rate of emigration from Armenia. “Unfortunately Armenia does not have a very reliable tool for measuring migration, which in itself is a serious problem for a country like Armenia, with its high level of emigration,” Garik Hayrapetyan, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) assistant representative in Yerevan, told the Armenian Weekly.

Ilona Ter-Minasyan, the head of the International Migration Organization’s (IOM) Yerevan office, agrees. “In most cases, Armenian migrants leave for the Russian Federation or CIS [Commonwealth of Independent States] countries. However, since a visa-free regime is applied to the CIS, emigration of Armenians is difficult to track, and therefore it is difficult to talk about [emigration] rates, which would be based on reliable migration statistics,” she told the Weekly.

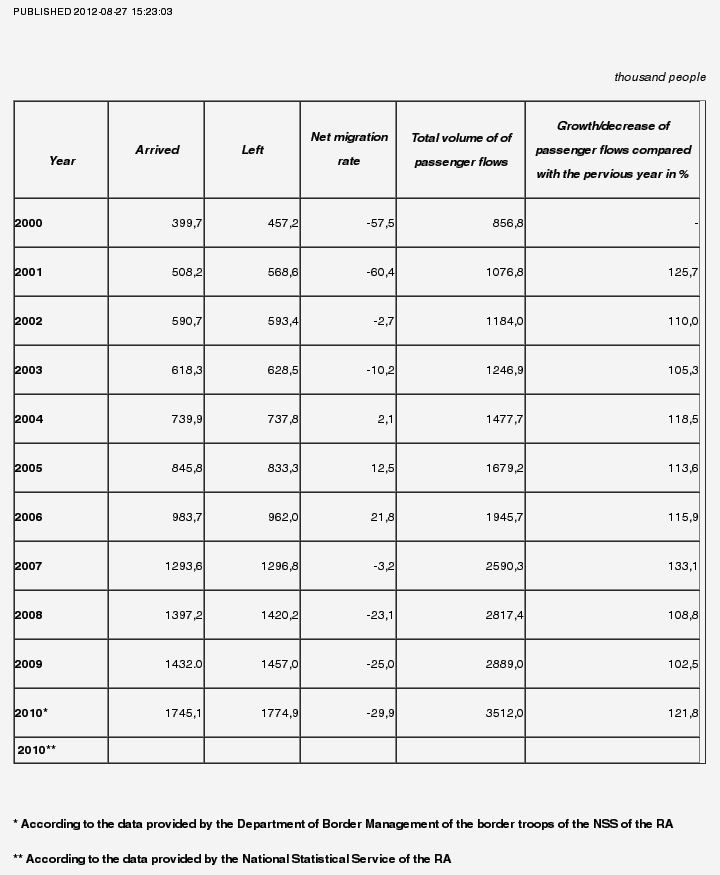

One method currently used to determine the migration rate in Armenia is a rudimentary head count of arriving and departing passengers, via airplane, railway, and highway. The balance—whether negative or positive—is used by many as an approximation of the migration rate. “[This] gives only quantitative data [that] is very hard to analyze for revealing the real causes for and the situation with migration. According to this tool, the country is losing approximately 1.5 percent of its population annually. The situation is aggravated when we add to this the fact that those who are leaving are at the most active reproductive and economic age. This is a very serious number for a country with a population of 3 million as it also influences the population structure,” said Hayrapetyan.

Gagik Yeganyan, the head of State Migration Service (SMS) at the Armenian Ministry of Territorial Administration, believes that relying on transportation data to determine the net migration figures can be misleading. “The international passenger flow is not the same as migration. They are completely different. Perhaps there is a similarity between them, but they are not the same… Many misinterpret the passenger data, and construct stories around it,” he told the Armenian Weekly during a phone interview. When asked why the SMS had labeled the difference between the number of departing and arriving as “net migration” (see Figure 4 below), Yeganyan said the column was mislabeled, and the appropriate term is “balance” (or hashvegshir in Armenian).

Based on the transportation data (airlines, railway, state highway), the net migration rate was estimated to be -57,500 in 2000; -60,400 in 2001; -23,100 in 2008; -25,000 in 2009; and nearly -30,000 in 2010 (see Figure 4).

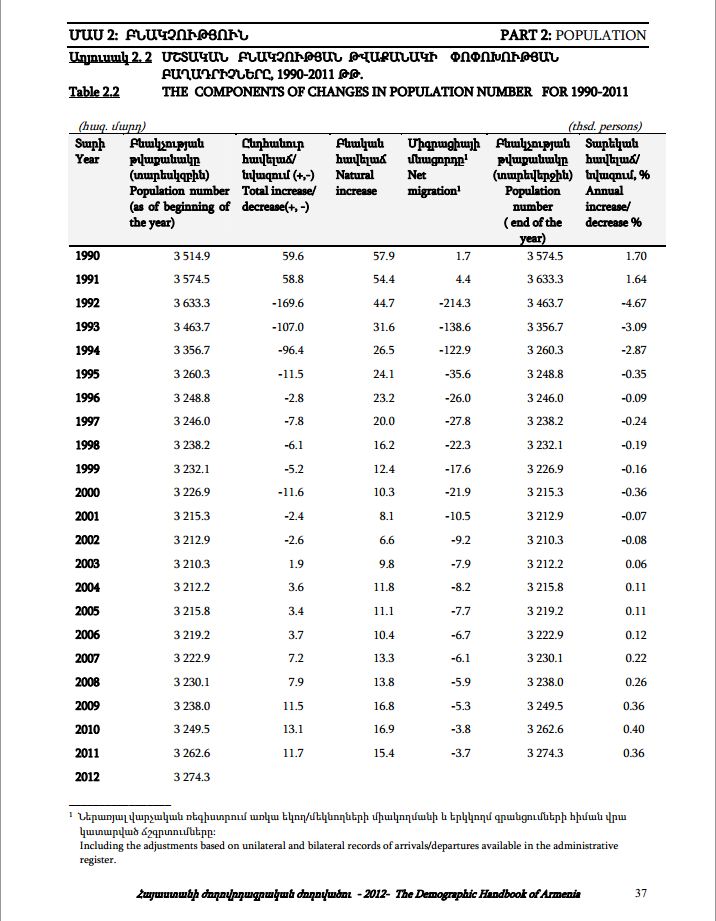

Alternately, the National Statistics Service of Armenia provides a starkly different set of data, with much lower emigration rate estimates. In the 2012 Demographic Handbook of Armenia (Part 2: Population), the NSS lists the following net migration figures: -21,900 for 2000; -10,500 for 2001; -5,900 for 2008; -5,300 for 2009, and -3,800 for 2010 (see Figure 5).

The Armenian Weekly reached out to the NSS for clarification on how the agency determined the net migration rate. “The data on migration of population, which are subject to administrative recording, were obtained from the processing of statistical registration coupons of administrative registrations from arriving and departing people—they are compiled according to the place of residence and during the registration write-off—from the regional passport services of Police under the Armenian government,” the head of the Population Census and Demography Division of the NSS, Karine Kujumjyan, told the Weekly (see Figure 5). “These indicators don’t fully reflect the real movement of population within the country. The population censuses, use [the data]—as a unique source of administrative official registration—for the periodical updating of the number of resident population,” she added.

Kujumjyan said the NSS also makes use of data on the transportation flow, although the data are unreliable. “In order to register the volume of population movement, we also provided users with information on summary volume of passengers’ turnover from air, road, and railway transport. However, as this data represent the fact of the border crossing (the same person could cross the border several times), rather than specific migrants, and because the basic data are not identified and don’t reflect the purpose and duration of departure or arrival, consequently they can’t be considered as migration data with international methodology. They reflect a registered passenger turnover balance with the quantitative difference of arrivals and departures for certain periods of time,” she explained.

Yeganyan, from the SMS, insists that the figures compiled by the National Statistics Service are the most “reliable yet general” data available on emigration. “The NSS data reflect the number of registered migrants, but they are only a small part of the larger picture. There are hundreds of thousands of people who have lived in Russia for years—5-10 years—but they are still counted as residents of Armenia. The NSS counts the de jure migrants, the registered ones,” he said, adding that this approach was also apparent in the registered voter list, which includes the names of long-term and temporary emigrants.

Figure 5

Source: NSS 2012 Demographic Handbook of Armenia http://www.armstat.am/file/article/demos_12_7-10.pdf

Between January and August 2012, the balance of people who arrived in the country (1,455,246) and left the country (1,477,246) was -90,799, according to the National Statistical Service of Armenia.3 That number was an increase of 20.7 percent from 2011, when the balance was at -75,200.4 Similarly, the Civil Aviation Department released their numbers for the first 8 months of 2012; their data showed that nearly 59,000 people flew out of the country and did not return, compared with around 62,000 the previous year. Reports speculated that the decrease could be explained by the 5,000 or so Syrian Armenians who arrived in Armenia during that period.5

Though reluctant, Yeganyan acknowledged that the passenger flow figures at the very least pointed to a problem (see Figure 4). “When you see the minus sign consistently in the balance—for four years in a row—then yes, it shows that people are thinking of emigrating,” he said, adding, “but you need a study to prove it… You have to always ask: What are the sources for figures on emigration? Sometimes, some people and political parties take advantage of numbers… People go to villages, see there are no lights in houses, and they become upset. Of course it is upsetting, but you cannot use that as a source.”

“Emigration goes on all over the world,” continued Yeganyan. “Here, people are too sensitive about this issue, but it also exists elsewhere. For instance, one study found that 48 percent of Brits want to leave England, the first reason being the economy, this according to the Sun. From the U.S., people immigrate to Canada and elsewhere. I’m not saying Armenia is better than the U.K.—not at all—but circumstances have changed. Migration has always been a part of human history… But we do have plenty of problems in Armenia; after all, poverty is at 30 percent.”

ILCS report on poverty and labor market

There have been other sets of studies that have aimed to clarify the rate and causes of emigration. The Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ILCS), funded by the state budget and the Millenium Challenge Corporation, is one such alternative source of data. “[The survey provides] information on the place of residence and reasons for leaving of household members aged 15 and over involved in the migration processes,” explained Kujujyan of the NSS.

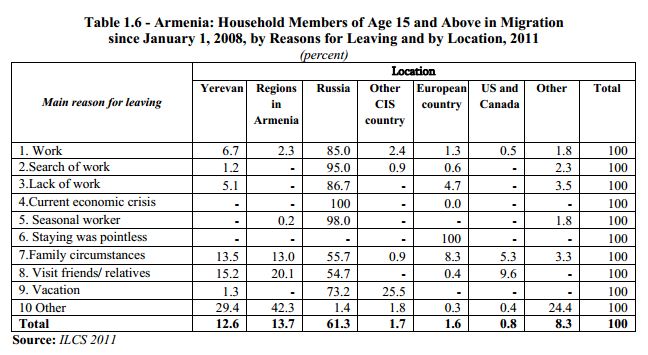

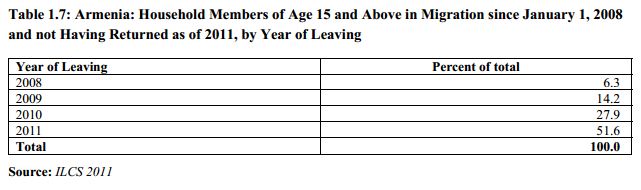

According to the ILCS study and based on their survey of 7,872 households, 61.3 percent of household members in external and internal migration since 2008 lived in Russia as of 2011; 12.4 percent in other countries; and only 26.3 percent in Yerevan or other regions in Armenia (see Figure 6). About 58.4 percent of all household members aged 15 or older were involved in international migration, and 41.6 percent were long-term migrants (one year or more; see Figure 7).

Figure 6

Source: 2012 Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ILCS), http://www.armstat.am/file/article/poverty_2012e_2.pdf

Figure 7

Source: 2012 Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ILCS), http://www.armstat.am/file/article/poverty_2012e_2.pdf

Survey on migration

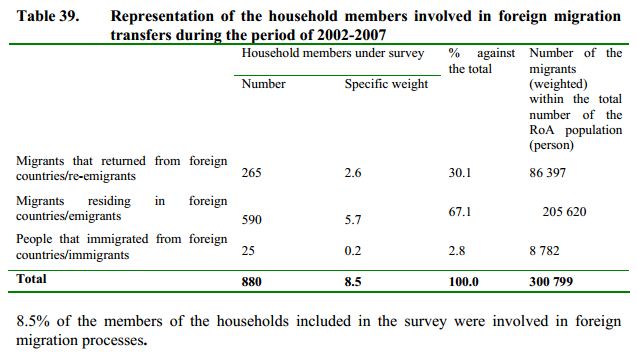

The 2007 “Report on Sample Survey on External and Internal Migration in RA” (henceforth, the “2007 Report on Migration”) is another important source on migration. The survey—implemented by the Ministry of Labor and Social Issues of Armenia and the NSS, and funded by UNFPA—evaluated changes in migration trends in 2002-07 that resulted from socio-economic reforms, and assessed “the quantitative and qualitative characteristics, socio-demographic and economic characteristics, and future migration plans of different groups involved in migration processes.” A total of 2,500 households were surveyed, of which 83.1 percent had “no intention” or “little intention” to permanently or for a long-term period leave their residence, while 5.3 percent were “definitely determined” or “probably would” leave permanently or for a long period (36.5 percent to Russia, 21.2 percent to the U.S., 11.5 percent to Ukraine, 5.8 percent to Georgia, and 13.5 percent to other states). About 8.5 percent of the surveyed household members were formerly involved in foreign migration procedures (30.1 percent of whom had returned from foreign migration, of which 62.3 percent were male, 37.7 percent were female, and 65.7 percent were between the ages of 20 and 49 with the average age being 35). Many—54 percent—of the foreign migrants surveyed considered their trip as “completely successful,” 27 percent as “unsuccessful,” and 19 percent could not tell.

Most migrants—56.7 percent—had worked in construction abroad, and 15.3 percent in commerce and trade. About 54.5 percent of them had worked abroad for up to one year, while their employment was legally formalized for 18.5 percent of the months they worked. Forty-nine percent of foreign migrants were temporarily registered in the foreign country they resided in; 22.5 percent had obtained an employment right; 6.6 percent had acquired citizenship; and 3 percent had applied as refugees or asylum seekers. Sixty percent of the foreign migrants had intended to return before the end of the year, and 18 percent had no intention of returning. From the migrants that were in foreign countries during the survey, 76.4 percent were in Russia, 9.8 percent were in European countries, and 4.8 percent were in the U.S.

The authors of the report extrapolated the survey results to the total population, according to which 86,397 persons out of an estimated 2,927,0006 residents in the country would have returned from foreign migration, and 205,620 would be residing in foreign countries (see figure 8).

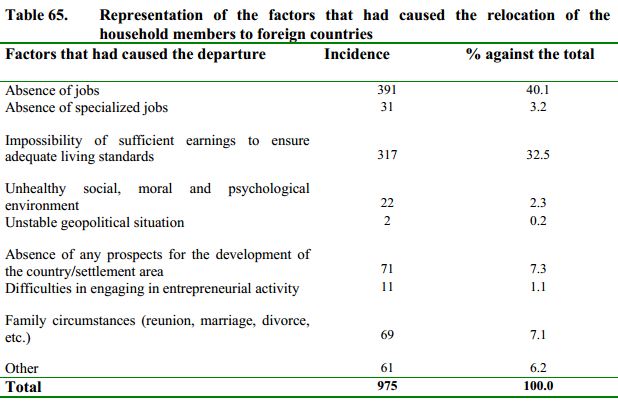

The survey also revealed the main motivating factors for citizens seeking life abroad. Quite predictably, the most cited reason was lack of jobs, followed by inadequate pay (see figure 9).

The lack of comprehensive data also hampers the possibility of effective solutions targeting the emigration crisis. UNFPA’s Hayrapetyan agrees that one of the main compounding factors is the socio-economic situation in Armenia. However, “[without] a qualitative tool for measuring migration…we were not able to reveal the causes,” said Hayrapetyan, adding, “Some of the causes might not be socio-economic, but rather related to the value [system and] psychological environment, such as feelings of non-security or social stigma. Unfortunately, those who are leaving because of the above-mentioned reasons are not the less-skilled workers but high-skilled professionals for whom economic hardship is not the real issue.”

Brain drain

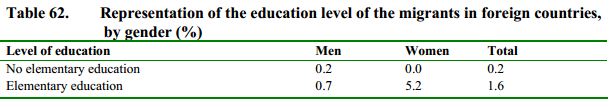

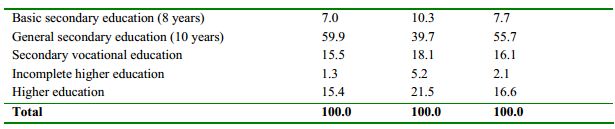

There is the fear that the country’s brightest are leaving for greener shores. According to the 2007 Report on Migration, 41.9 percent of external migrants had secondary education, 24.8 percent had secondary vocational education, and 21.1 percent had higher education (see figure 10 below). In fact, according to the World Bank Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011, Armenia was ranked 5th out of the top 10 countries with the highest rate of emigration among people with tertiary-education; Armenia’s emigration rate among this group was 8.8 percent (after the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (29.1 percent), Bosnia and Herzegovina (23.9 percent), Romania (11.8 percent), and Albania (9.0 percent)).

A 2008 survey funded by the OSCE Yerevan office and titled “Return Migration to Armenia in 2001-2008” broke down migrants by professional profile. The study surveyed 2,500 households, and found that 10 percent of Armenia’s skilled labor, or 90,000 people, had left Armenia in the period of 2002-07.7

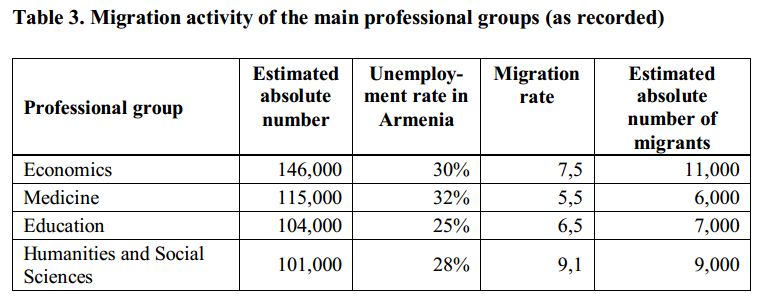

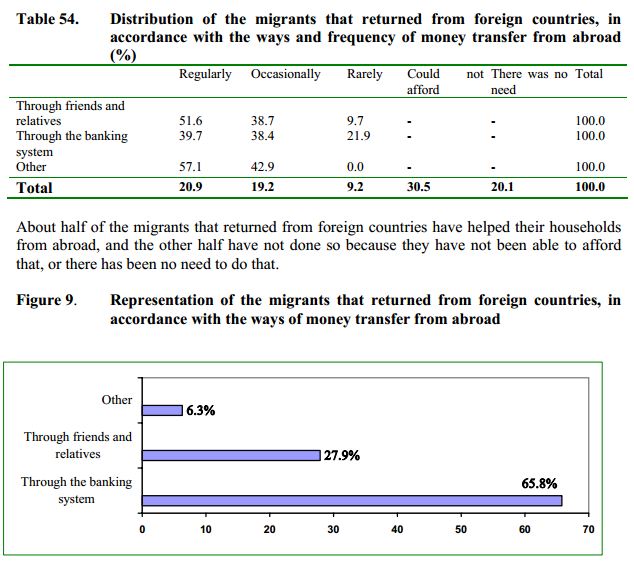

The survey found that migration trends aren’t solely affected by competitiveness in a specific professional group in the domestic labor market, but also by demand in the destination countries—mainly Russia—as well as better wages. IT professionals, for instance, have a low migration rate as the demand for them is high in the country; additionally, IT jobs can be outsourced. The migration activities of economists, doctors, teachers, and specialists in the humanities and social sciences (mostly lawyers)—together making up 52 percent of the skilled labor force—are affected by different variables: These professions have a high unemployment rate, because there simply are not enough jobs for them, but foreign labor markets cannot absorb them either. Some migrants working in these professions instead choose to take on less skilled jobs. On the other hand, most—“the overwhelming majority”— working in the food technologies, and the textile and light industries are women (40 percent unemployed) and they are less likely to find work abroad (see figures 11 and 12 for the breakdown of migrants by profession).

In 2012, Armenian Minister of Education and Sciences Armen Ashotyan reportedly told up-and-coming scientists to build their careers abroad. “It would be preferable that you, a physicist with a bright future, go to Chicago or Boston and make a name for yourself. Afterwards, you will be in a better position to help Armenia through your contacts and grants, rather than staying and working as a laboratory assistant somewhere. Right now the government cannot guarantee the condition necessary for your career path,” he was quoted as saying by Hetq. The author of the article, Heritage Party member Daniel Ioannisyan responded, “It seems that our government is not interested in maintaining an intellectual segment of society. The regime appears more intent on creating a nation of waiters, cab drivers, laborers, miners, car washers, and cops, since–with all due respect to the former–it’s easier for the regime to control them. We cannot let the powers that be continue their policy of driving out what remains of Armenia’s intellectual class.”

Government response

The migration rate has also given way to a blame game within the government and the opposition. Secretary of the Armenian National Congress (ANC) and MP Aram Manukyan accused the current ruling coalition of facilitating migration, as 69,000 people had left the country from January to June 2012, and that number could reach 150,000 by the end of the year, they said. In response, Prime Minister Tigran Sargsyan said the government did not have a “conspiracy plot.” Sargsyan retorted that the greatest wave of migration occurred in the early 1990’s when the ANC held power, and added, “As a matter of fact, migration volumes started to decrease parallel to the increase of economic growth. However, the 2009 crisis had a negative impact on stimulating the migration.” Sargsyan assured that the government was working on creating new jobs and increasing living standards in the country.8

Manukyan raised the issue of emigration once again in November 2012, saying it should be a main discussion topic in the upcoming presidential elections. He also promised that the ANC presidential candidate—believed at the time to be former President Levon Der Petrosyan (who will in fact not run)—would be able to tackle the issue. He also claimed that the current emigration figures are but 40 percent of the real numbers. “If years ago people were leaving Armenia because of social issues only, today they are leaving because of not seeing any prospect, [or] stability,” he said. “Everyone should put aside his ambitions. Armenia is being emptied. Unless the ruling authorities choose the consolidation path, the result will be irrevocable. These authorities have already failed in this issue. The only way to stop emigration is to overthrow the authorities,” he added.9

In July 2011, President Serge Sarkisian said that during the preceding 10 years, emigration had become constant, especially in the case of seasonal migrants. “The main factor that concerns us is the negative difference between departures and arrivals of the citizens, as more people leave than return. About 57,000 people did not return to Armenia in 2000; the number was 60,000 in 2001. However, positive trend was registered in 2004-06. As a result, 23,000-29,000 people did not return to Armenia during the last years,” he was quoted by news.am as saying. He added that the best way to combat the problem is by fighting against factors that drive people out of the country.

To encourage population growth and also tackle the issue of low birth rates in the country (currently below the 2.15 children per female required to maintain the current population number), the government has formulated an action plan that entails offering preferential mortgages to newlyweds, and increasing the birth allowance to $2,400 for every third and fourth child, and $3,600 to every fifth child. Currently that allowance is at $120 for the first two children, and $1,000 for additional children, reported news.am.10

However, for a solution to work, it has to be a long-term one. “In order to deal with the issue, the government must get rid of the causes for emigration. Economy is the main reason: poverty, lack of jobs, and difficulties in starting businesses. About 70 percent of the people leave because of this. Others leave for other reasons, such as a lack of hope in the future,” said Yeganyan of the SMS. “We get asked, ‘Why won’t the government draft laws to halt emigration?’ That is ridiculous. Imagine if someone were to tell you, you cannot leave the country…” he added.

Hayrapetyan of UNFPA, like Yeganyan, agrees that the government should not restrict movement, but rather, manage it. “The government tries not to control but manage the migration flow, which to me is the right action. The effectiveness of the government’s actions is a different issue, but the direction is right. The point is that prevention of migration is a very complex problem and it cannot be solved overnight. So as Armenian migration is mainly labor migration, it is important to make sure that links are preserved between the migrants and the state by making sure that the state plays an important role in defending the rights of its citizens in other countries, and helps to ensure legal contractual relations and makes migration cyclical,” he said.

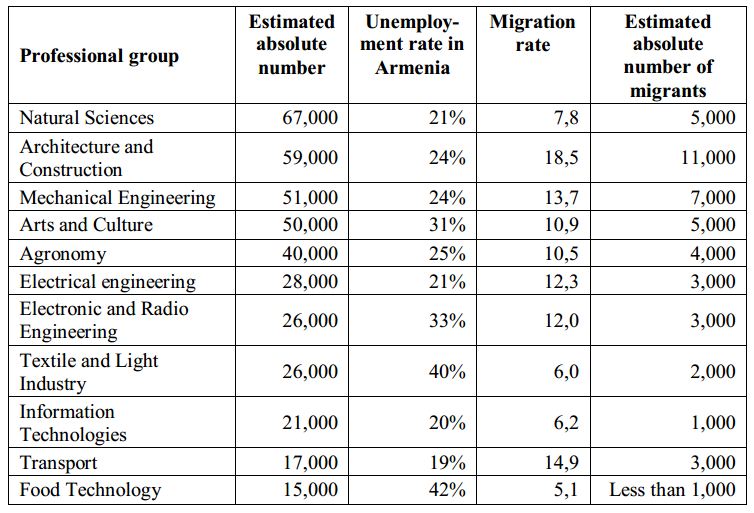

In fact, the 2007 Report on Migration revealed that 7.3 percent of the surveyed migrants had their passports confiscated during their stay in a foreign country, 60 percent of them had not been familiar with legislation pertaining to their rights as migrants, and 84.6 percent had not applied to any entity—including the Armenian authorities—for support when they were found in difficult situations (see figure 13).

To help the government better cope with the migration issue, the IOM prepared the Migration Management Assessment Report in 2008, which provided the government with a broad range of recommendations to tackle the issue more efficiently, said their Yerevan office head Ter-Minasyan.

Meanwhile, as a first and crucial step, the government is at the early stages of initiating a project to compile a registry of emigrants. “The source for data on emigration is studies and surveys, including from sociological organizations and international organizations such as the OSCE and UNDP, and not registrations. Undertaking such a project costs money—it requires field work and interviews, and thousands of people need to be surveyed. For the first time, the government has approved, in its 2013 budget, that such a study be funded, not by the SMS, but by [third party] professionals. The budget will be on the table soon, I trust they will keep that on there,” said Yeganyan, whose department in August had proposed to the government to carry out a study on the matter to get a clearer picture of the migration rate in Armenia.

Yeganyan takes the matter to heart. “For me, even one person emigrating is a problem; for others, tens of thousands of people isn’t a problem. Emigration brings with it social, economic, and national security issues,” he said. “However, there is no sound data out there about the rate of it in Armenia,” he repeated.

Remittances for survival

Remittances sent home by migrants from Armenia were estimated to be over US$1 billion in 2008. Remittances constituted about 9 percent of Armenia’s GDP in 2009 (US$769 million), according to the World Bank Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011.

Today, Lilit resides in New England, as do her daughter and three grandchildren. Lilit’s two other children live in Russia with their families. Lilit’s husband and her mother are the only remaining family members in Armenia. “My husband drives a marshutka [minivan] and is barely able to take care of his own needs,” she said. Now, Lilit works every day. For the first eight years she cleaned people’s homes. Last year she found a full-time job in the textile industry, and another part-time job in the same field. She works around 12 hours a day, earning $17 an hour from one job, and $150 a week from the other. “It’s a much better job than bread baking,” she smiled. “I send a portion of my earnings back home, because they need it. Without our help they can’t survive,” she said.

As a pensioner, Lilit’s elderly mother receives less than $100 a month, which her daughter says is insufficient to cover the bills—utilities, and the rising prices of food—let alone medical expenses. “My mother is a pensioner, but she pays for electricity and gas, and the money runs out fast, leaving her waiting for her next monthly payment. The other day, they said on TV that the pension was being increased by around 30,000 dram, but the price of food has also gone up,” she said. “My mother was just in the hospital. She had her hip replaced. If I hadn’t sent her the $2,000, no one would have cared for her… If I had never left Armenia, if I was still living there, how would I have been able to pay for it?” she asked.

“While the remittances sent to Armenia help the migrants’ families to solve some of their financial problems, a large amount of these resources is used to cover their immediate needs. Investment in longer term sustainable economic activities is apparently limited,” summarized a 2008 report by the International Labor Organization titled, “Migrant Remittances to Armenia: The Potential for Savings and Economic Investment and Financial Products to Attract Remittances.”

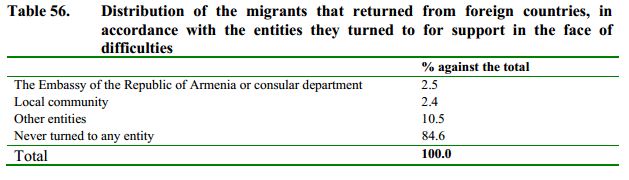

The study surveyed 1,000 households that have a family member in migration. Seventy-five percent of them had one migrant family member; four percent had three or more. About 70 percent of households with migrant family members abroad received remittances; around one fifth of them received it every month. For the overwhelming majority of these households (80 percent), more than 90 percent of remittances were used to cover everyday expenses. Eighty-five percent of households were unable to save any portion of their income, while 9 percent saved up to 20 percent. These savings are rarely kept in banks. However, there are a number of banks that focus on money transfers, targeting migrants. For instance, the Armenian Anelik Bank, with 13 branches in Armenia and 1 in Moscow, caters to Armenian migrants in Russia, allowing them to send remittances without opening a bank account, and for a low fee. The bank guarantees that the money will arrive to its destination within 1-24 hours.11 According to the 2007 Report on Migration, 65.8 percent of surveyed migrants said they used the banking system to send money back home (see figure 14).

The Russian way

Recently, Lilit’s brother, along with his wife, their two children, and grandchildren, were also “forced” to move abroad. Unemployment had eroded her brother’s will to stay, and he decided to try his luck in Russia. “He used to say, ‘I won’t leave my Armenia. Armenia is a good place.’ But he was out of options. He now works in construction in Russia,” said Lilit.

Most migrants from Armenia—some experts argue as much as 90 percent12—choose Russia as their destination.13 Like Lilit’s brother, many of them—around 40 percent—work in construction.14

Russian authorities see a solution to their own demographic problems in immigration. Russian President Vladimir Putin on Sept. 15, 2012 signed a decree15 giving new incentives for “compatriots” from former CIS countries, including Armenia, to relocate to Russia as part of his government’s “Fellow Countrymen” Program (also referred to as the Compatriots Program), which—as stated on the Kremlin’s official website—“aims to harness the potential and capabilities of compatriots abroad to the development needs of Russia’s regions. The program adds to the series of measures being taken to stabilize Russia’s population, especially in regions of strategic importance for the country.” During the Fourth World Congress of Compatriots, Putin reiterated his government’s commitment to providing aid to those wishing to make the move. “Assistance in moving to Russia will be provided for those who want to work or study in Russia, plan to open their own business, as well as individuals with outstanding achievements in science, technology, and culture, and with unique management experience,” he said.16

The Armenian Migration Service puts the number of applicants to the Compatriots Program at over 26,000, about 1,500 of whom have given up their Armenian citizenship to move to Russia.

According to data from the Armenian Migration Service, during the past four years the Compatriots Program in Armenia had a total of 26,000 applicants, of whom 1,500 have given up their Armenian citizenship and moved to live in Russia.

Prime Minister Sargsyan voiced his concern, noting the topic had been raised with Russian counterparts. “We have expressed our clear position. It is known to the political leadership of Russia. The ‘Compatriots’ program will no longer operate in Armenia in this format. The activities of such an organization in Armenia are not permissible,” he said.17

At a news conference, Russian Ambassador to Armenia Vyacheslav Kovalenko was asked why Russia refuses to suspend the “Fellow Countrymen” Program. “Does anyone drag the Armenians to Russia? Does anyone force them to go there? Do you think people will stop going if we end the program?” responded Kovalenko, who characterized the reactions to the program as “fuss” and “rumor.” “Why doesn’t anyone ask how the U.S. Embassy works? I can say that the Green Card has helped more people leave Armenia… Since 2007, more than 5,000 people have left Armenia with their families due to the Green Card,” he said, claiming that in comparison less than 5,000 had left for Russia. The program, he added, was to manage migration, and to ensure “normal” living conditions and salaries for the migrants.18

Irregular migration

In 2005, studies put the overall number of irregular migrants to Russia between 3 and 5.5 million, while migrants with proper documentation numbered only 300,000. “Many of these migrants are filling a niche in the Russian labor market by doing jobs that Russians do not want. At the same time, labor migration and remittances sent to families have become a survival strategy and a financial safety net,” according to the “Handbook on Establishing Effective Labour Migration Policies in Countries of Origin and Destination,” a joint project of the OSCE, IOM, and ILO.19

Armenian citizens are also engaged in irregular migration. “Armenian migrants often find themselves in irregular situations,” said Ter-Minasyan of the IOM. “In the IOM, we refer to someone who, owing to illegal entry or the expiry of his or her visa, lacks legal status in a transit or host country as an irregular migrant. The term applies to migrants who infringe on a country’s admission rules and any other person not authorized to remain in the host country… Indeed, this is an issue [for Armenia],” she explained.

When Lilit’s son moved to Russia, he, too, became an undocumented worker. “The government passed a law that all young Armenians in Russia should return to Armenia. The police would catch them and after paying fines they would be deported. But the money that he made was sufficient for him. He lived in a Russian village where he worked under the table in construction along with other Armenians,” said Lilit.

Her son eventually married a Russian woman, with whom he had a child. Four years later, he moved his family back to “his Armenia.” He wanted to give it another try. He found a job in construction, but work was sporadic: One day of work would be followed by a week of idle sitting and no pay. Frustrated, he tried his luck in carpentry, building tables and chairs. Again, work was scarce. Unable to support his family, he took his family back to Russia, where he now works in construction.

The housing construction sector was the first to be hit in Armenia following the global economic crisis, when the teal GDP dropped by 14.1 percent (GDP grew 2.2 percent in 2010, and 4.7 percent in 2011), according to the 2012 ILCS survey. “The sizable downturn of construction in 2009 (41.6 percent) accounted for 74.5 percent of GDP reduction, decreasing its share in GDP to 18.6 percent. In 2010, positive changes observed in this sector resulted in 3.3 percent growth rate over 2009; however, share of construction within GDP still remained low (17.3 percent), as compared to 25.3 percent in 2008.”

Emigration and the media

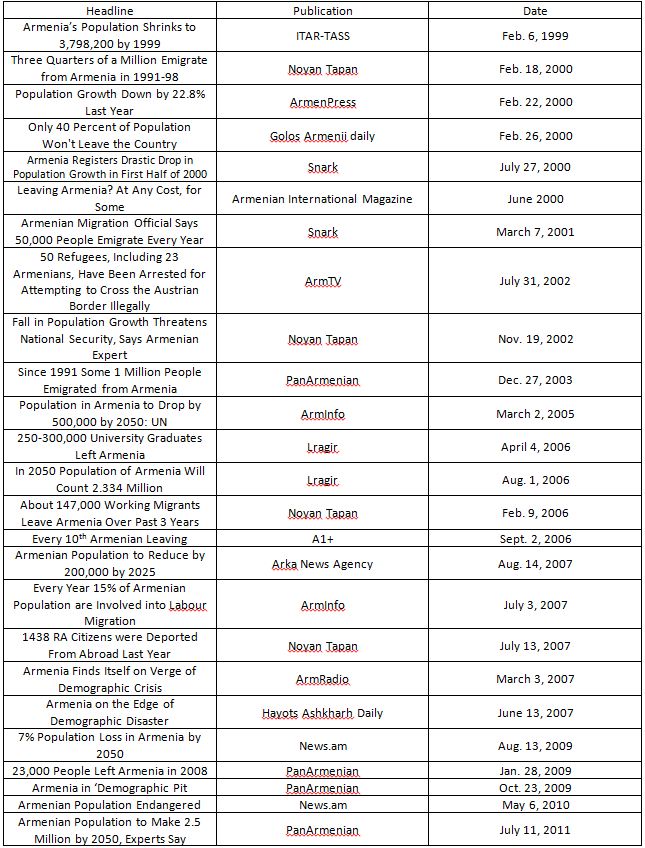

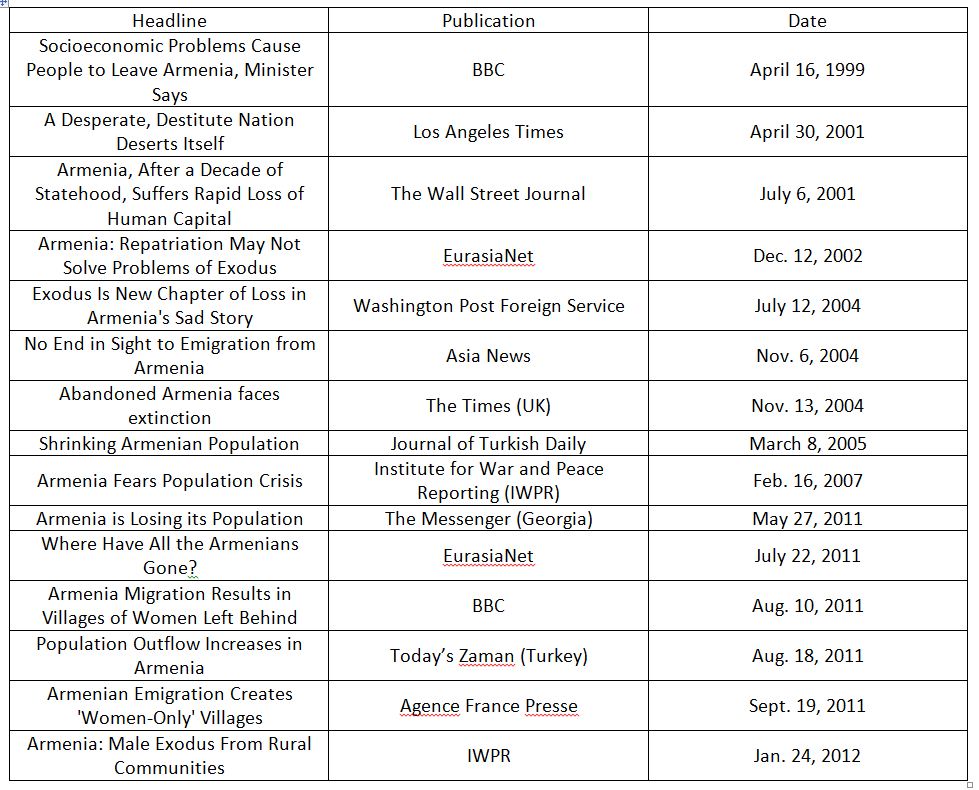

Despite the lack of reliable figures, there is serious concern that the population is diminishing at a worrisome rate. Over the past decade, nearly every perceived or expected change in population growth figures—pertaining to death, birth, abortion, marriage, divorce, and migration—brought with it articles, commentaries, and projections in the media. The nation, in turn, like shareholders in the stock market, watched these numbers in constant fluctuation. Headlines appearing in the Armenian news were disorienting, while the ones in the international media were no less alarming (see tables below).

Reactions in the domestic media:

Reactions in the domestic media (The Armenian Weekly would like to thank Dr. Ara Sanjian for providing us with a comprehensive list of articles on emigration from Armenia published since 1999)

Reactions in the international media:

Reactions in the international media (The Armenian Weekly would like to thank Dr. Ara Sanjian for providing us with a comprehensive list of articles on emigration from Armenia published since 1999)

For love of country

Lilit believes that if the situation in Armenia improves, others like her would return, and families would reunite. “If they only give us a way to stay—create jobs, improve the conditions a little—people will return. I, for one, would go back. My kids would go back as well,” she said, despite having a Green Card.

Lilit says she wants an Armenia where there are jobs and fair wages. She also wants a little bit of justice. “Without justice, it will be hard. If there is justice from the top, and things go into order, Armenia will be better. These things have to come from the government,” she said firmly. “If they were a little just and didn’t favor a few people… One person owns the gas industry and hosts a wedding that costs millions, and on the other hand you have someone whose child goes to bed hungry. If they give the people a chance to live—my people are a hardworking people—they will work again, and they will get back on their feet,” she added.

Despite the contentious figures on emigration, most experts agree that there is substantial reason to worry, and that steps must be taken to reduce the rate of emigration from Armenia. Migration management is one approach, a necessary one, but one that only deals with symptoms. The response must be multifold: Widespread reforms to uproot corruption from state institutions will both attract investment to the country, in turn creating jobs, as well as give people the hope they need to stay. As Yeganyan said, “Small steps—like drops of water—will eventually make a difference. Steps like reforming the police force, helping businesses grow, opening factories, and building roads…”

Notes

1- Name has been changed to protect privacy.

2- The World Bank Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLAC/Resources/Factbook2011-Ebook.pdf

3- Lragir.am, “90 Thousand People Left Armenia.” Sept. 20, 2012. http://www.lragir.am/engsrc/country27442.html

4- Lurer.com, “’Haykakan Zhamanak’: Emigration from Armenia Continues.” Sept. 18, 2012. http://lurer.com/?p=41823&l=en

5- News.am, “Emigration from Armenia Continues—Newspaper.” Sept. 14, 2012.

6- Source: 2012 Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ILCS), Part 1- Armenia: Poverty Profile and Labor Market Developments in 2008-2011.

7- The sample size, argued the survey conductors, guaranteed a 2 percent margin of error with a confidence level of 95 percent, given that there are a total of 778,666 households in Armenia according to the 2001 census.

8- News.am, “Armenian PM Does Not Motivate People to Leave Country.” June 20, 2012.

9- Tert.am, “Armenian National Congress to Discuss Candidate Issue Unless Levon Ter-Petrosyan Refuses to Run for Presidency.” Nov. 5, 2012.

10- News.am, “Armenian Government Plans to Stimulate Birth Rate.” June 20, 2012.

11- Sources: http://www.anelik.ru/bank/, http://www.anelik.am/eng/

12- Participants at a roundtable discussion hosted by the Republican Union of Employers on Aug. 21, 2012.

13- Lragir.am, “90% of Armenian Migrants Leave for Russia.” Aug. 22, 2012. http://www.lragir.am/engsrc/society27150.html

14- According to the 2009 ILO report, “Migrant Remittances to Armenia: The Potential for Savings and Economic Investment and Financial Products to Attract Remittances.”

15- News.am, “Russian President’s Decree to Give New Impetus to Emigration from Armenia.” Sept. 27, 2012. http://news.am/eng/news/122559.html You can find the official news here: http://eng.kremlin.ru/news/4416

16- Official website of the Kremlin: http://eng.kremlin.ru/news/4562

17- ArmeniaNow.com, “End of “Compatriots”?: Government says Russian immigration program unacceptable for Armenia.” Oct. 4, 2012. http://www.armenianow.com/society/40234/russian_program_compatriots_concerns_armenia_labor_migration

18- Tert.am, “No One Forces Armenia into Migration—Russian Ambassador.” Oct. 9, 2012.

19- Handbook on Establishing Effective Labour Migration Policies in Countries of Origin and Destination.” Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), International Organization for Migration (IOM), International Labor Organization (ILO) Department of Communication and Public Information. 2006